This Q&A is part of the Fraud Fighters Manual, a collective set of stories from Fintech fraud fighters. Download your copy of the Fraud Fighters Manual here to read the full version.

Are there people or organizations more likely to be targets of fraud?

I think it tends to be concentric around where there’s somewhat of a fungibility in the asset that they’re stealing. So, lending is always a high-risk profile for fraud because the outcome is receiving cash, which is very easy to move and get away with.

There can be high-value, very fungible physical goods that are easy to move. And I think those are known as high fraud-risk items. A diamond necklace, for example. There are complications with that type of fraud that require the fraudster to have reshipping fraud as a part of their process, in terms of having a valid address to ship the item to and then ship it overseas or wherever the fraud is occurring.

So, physical fraud increases logistical complexity and improves failure rates. But it really is just a kind of basic economic calculation of what’s the gross margin on the stolen identity that I have. Anywhere where that calculus becomes net positive, I think you’re going to find fraud. People are willing to take things for free regardless of how low value you may perceive them to be. Free is still free.

Have you ever been surprised by a fraud?

Earlier in my career, I’d think of physical documents as being maybe fakeable but obvious when they are faked. And now I think that is wildly untrue.

Any physical documentation requirement upload—like a pay stub or a bank statement—to accomplish anything, there will always be a boatload of fraud in those environments. You can see really advanced editing methods and/or finding valid formats for distributing that information.

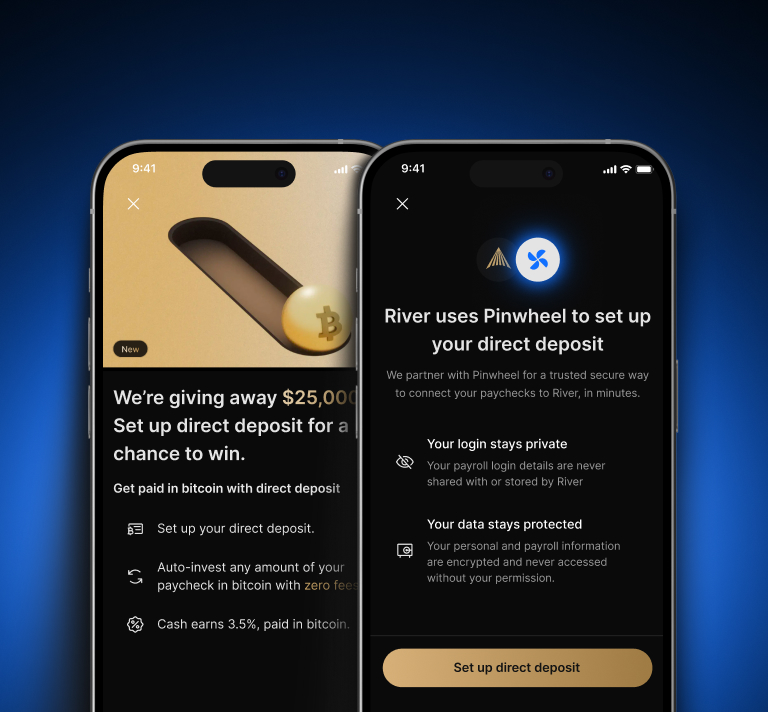

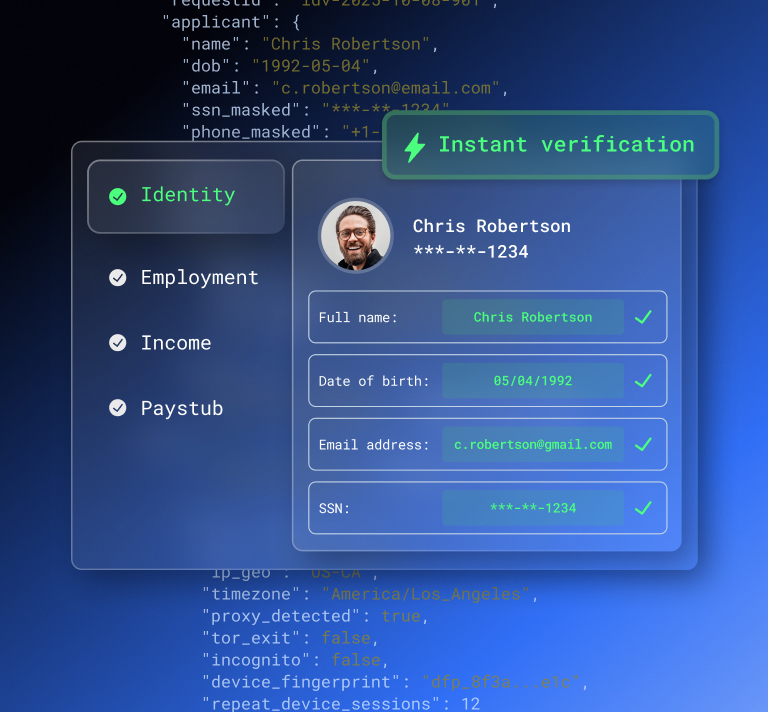

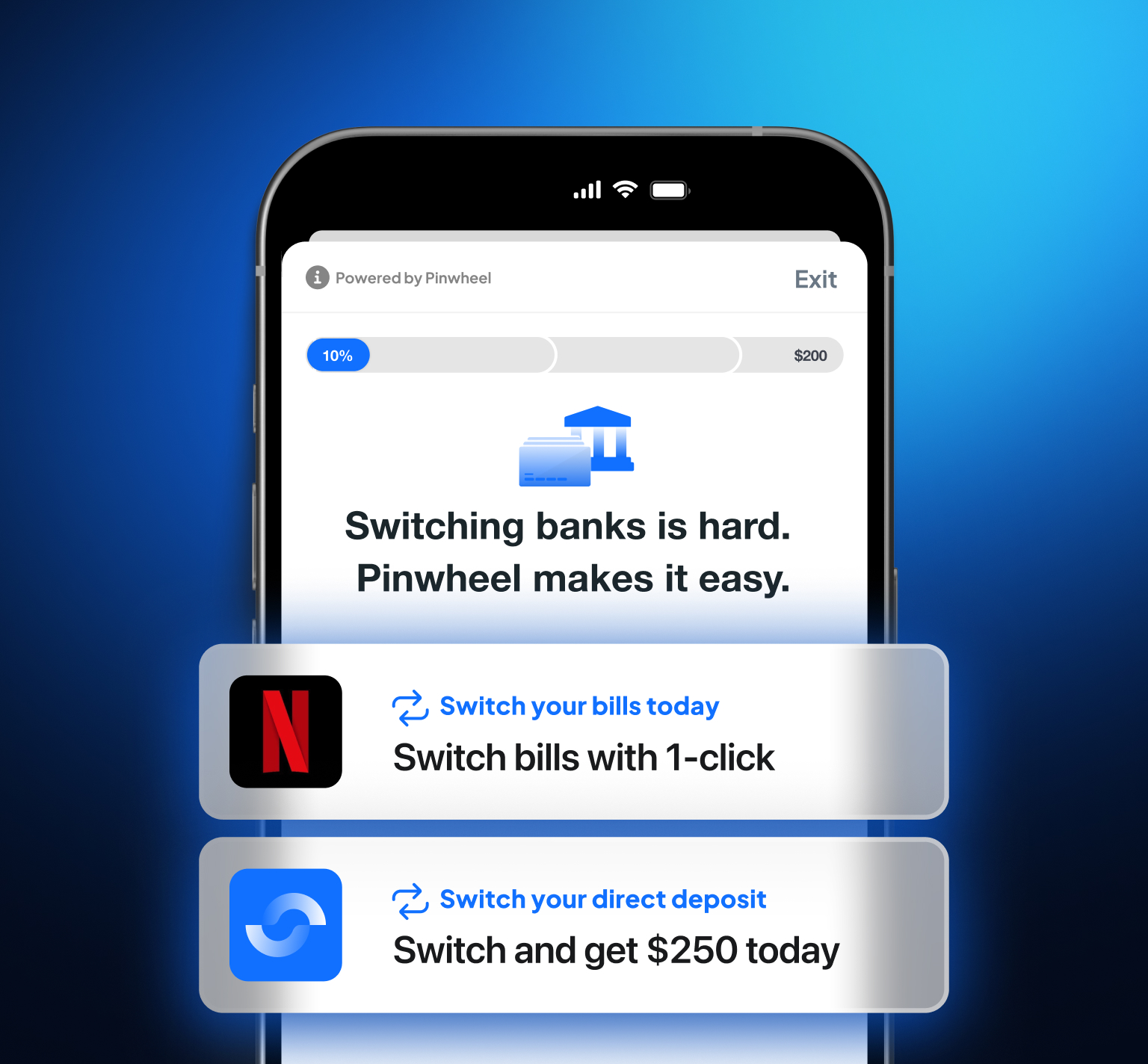

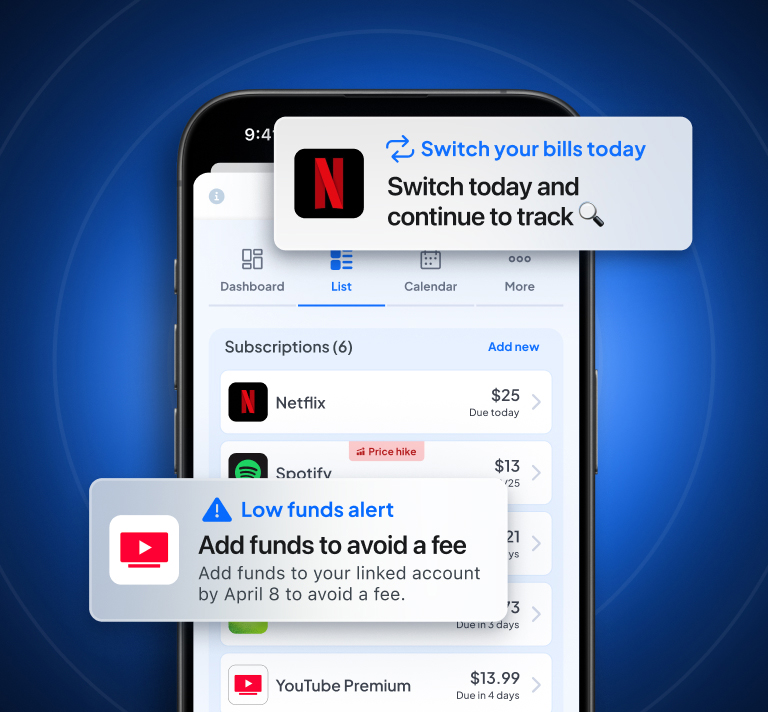

When I was a little younger, I was very surprised to find the amount of effort that the fraudsters would and could put into making those documents appear to be pure and valid. And you know, you have companies like Pinwheel today that give you access to the “source of truth” information that makes it that much more difficult for frauds. You kind of take out the middleman. You’re not uploading documents; you’re receiving them from the source.

But on the other side of the equation, something that really, really surprised me was that fraudster ring that was extorting actual people to take out loans. You have these cohorts of consumers who are objectively good and show no fraud patterns. They have normal behavioral characteristics; they don’t fit into any of the normal first-party fraud characterizations.

And you are just questioning: Why are there so many problems with this cohort of users?

When you figure out what’s going on, it’s somewhat terrifying. It’s a movie scenario: someone essentially with a gun to their head, being told to do fraudulent things. That is happening in the real world, and it’s very hard to stop.

What are the most vulnerable processes fraudsters most frequently target?

They target physical documentation. They target humans as a point of weakness.

They will actively try and get pushed into call center operations or customer service agents to evade policies that are in place and try to reverse engineer them. And they are boisterous, and people fold under the pressure of someone being boisterous and maybe give them information that they shouldn’t have.

I think humans are always the greatest point of failure—anywhere where human process is involved. And that tends to be like physical documentation in person or contact center interactions.

Fraudsters are becoming better and better, and the digital detection side of it is becoming more difficult.

How do you see fraud continuing to evolve in the future?

I think the fraud prevention strategies that most people have available, and the types of data sources that most companies use to try and verify identities, have been relatively stagnant for quite a long time.

Outside of the behavioral characteristics, I have your email address that I can maybe verify the longevity of and the quality of. I have your phone number that I can verify the longevity and quality of, and I can even potentially call it.

But I think the prevention tactics become more well-known, and people rely very heavily on those types of passive verification tools and things like device fingerprinting to stop large fraud rings. But the more well-known the tools are, the more readily available ways to evade those tools become.

And I do personally worry that the innovation on the prevention side is slower than the innovation on the attack side. The tactics that currently exist are somewhat in terms of their effectiveness, and people need to start becoming a lot more invested in things like AI and machine learning to help really stop fraud in a more effective manner. Basic business logic is no longer going to cut it.

Are there any common mistakes or assumptions you commonly run into regarding fraudsters or fraud?

Organizations tend to not have dynamic enough policies in place to stop fraud. I think the fraud is going to adapt very quickly to the choices that you’ve made to prevent it, and you may feel great about the fact that you’re preventing a known set of fraud, but I think it gives you a false sense of security. And I think for companies that I’ve worked for or worked with to try and help them build better strategies for fraud prevention, you find that they think fraud is more of a “set it and forget it” type of relationship. I think that is very disingenuous to the state of the ecosystem.

On a more tactical level, I’ve encountered companies that think that certain types of verification tools can be relied on very heavily, things like biometric authentication, or take a picture of yourself, take a picture of your driver’s license. They think that it’s not possible for fraud to exist in channels where those tools exist. And I think that is also like a fatal assumption to assume that any of your tools are perfect in their ability to prevent fraud.

Tell us a little about the different types of fraud you encounter in digital environments.

Broadly speaking, everyone says first-party fraud and third-party fraud, but I think there’s a lot more nuance to that.

There’s true first-party fraud where the person has no intent to repay. In a lending environment, it’s sometimes called friendly fraud as well.

There’s also family fraud, but it doesn’t feel quite honest to place it next to true ID theft or actual fraud rings. Family fraud is when you have someone who is very close to the victim and can easily represent their identity, misrepresenting the state of their interest or needs. And that could be a spouse, caregiver, or another family member.

Then you have true third-party fraud, obviously with ID theft. It can manifest primarily digitally—in the form of information gleaned from the dark web or stolen information from phishing websites—but it can also manifest physically in the real world.

And I’ve actually had experience with this where we had fraud rings that were operating in different states in the United States. They were going to people and putting weapons to them and saying, “Apply for these loans, and we’re going to take the proceeds and run away with them.” So, it’s, in some sense, first-party fraud because it was real information, but it truly was a third-party fraud ring that was manipulating first-party actors into committing the fraudulent deed.

And then, an entirely separate type of fraud, synthetic fraud, combines real and/or fabricated identity characteristics to effectively spoof the credit reporting agencies into creating “Frankenstein” identities. And that’s a separate problem that is generally more resolvable through vendor relationships and/or data analysis.

What is the most common type of fraudster seen in fraud prevention?

The most common that people quantify is third-party fraud because it tends to come with the strongest external dependent variable, which is people filing things like ID theft claims.

The things that go most underrepresented are likely first-party fraud. In a typical lending environment, they will often get rolled into normal delinquencies because it’s very difficult to suss out the difference between credit risk, for example, and unwillingness to pay in the context of a loan environment.

Synthetic fraud is very difficult to identify purely because there is no one adversely affected by the fraud. There is no true identity that is kind of potentially exposed to loss, and the recourse of marking up someone’s credit report is nothing when that person doesn’t exist.

Are there any atypical types of fraudsters that you’ve encountered or that you see emerging?

You allow normal good people to open accounts, take loans, whatever it may be in whatever the context of your business. And then, those individuals get phished, and fraudsters take over their accounts or manipulate call centers or operation centers to take negative action against those accounts.

I think there’s definitely an uptick in that threat vector, primarily because a lot of the prevention methods tend to exist at the top of the funnel for businesses. So, once an account is open and the person seems to be good, it’s tough to reevaluate that constantly, and it creates opportunity for fraud when the focus is elsewhere.

Do you think companies have robust enough KYC/KYB policies? Why or why not?

Generally speaking, in my experience, if you take KYC as an example, the regulatory requirements for KYC are fairly broad: “Do you feel confident that you know the person who is applying for a loan?” The methods that companies use to satisfy their KYC requirements vary quite widely and, in my experience, tend to be somewhat derivative—or at least additive to actual fraud prevention methodologies.

How do you say that the person that you are looking at is not falling into any of the groups discussed above? The legal requirements are fairly thinly veiled in terms of whether you feel reasonably confident that you know who the person is and that this is the person who they say they are. The only way to really accomplish that is to layer multiple types of fraud strategies into place. You have to create a tiered approach, layered approach, and targeted approach to stop all these different kinds of fraud.

In the case of KYB, where you’re verifying the legitimacy of a company or organization to assess the risk of doing business with them, that’s more acutely associated with the actual legitimacy of the business. In that sense, just meeting the bare minimum of the legal requirement is not going to be nearly enough actually to prevent and mitigate fraud.

What provides the most friction when companies create KYC/KYB policies?

I think the main friction point is that if you want no fraud, you’ll have no volume run through your business.

Where do you decide the right management point is for acceptable risk tolerance beyond meeting the KYC requirements? I think every business activity does meet those requirements. But if we’re truly talking about fraud prevention above and beyond, the friction really exists. And how much friction do I want to introduce to my process to try and become incrementally savvier to fight against the different types of fraud? Managing those cutoffs and trying to get accurate dependent variables to model and/or evaluate against is very, very difficult.

What real fraud looks like can be hard to determine. In the case of first-party fraud, how do I know someone is defrauding me? How do I know they had an unwillingness to repay? Creating a definition to surmise that is very hard because the person won’t tell you, “Oh yeah, at the time that I applied for this, I had no intention to repay.”

I think, on the KYB side, it’s largely that institutions are somewhat disincentivized from wanting to weed out potential clients or potential vendors. So, you have to create a system of true governance. One that can have the right kind of checks and balances in place to ensure that the motivations of individual employees to solve a specific problem are not the antithesis of what your KYB strategy needs to be successful.

What do you think organizations most commonly get wrong about their KYC/KYB policies or strategies?

I think organizations on the KYC side don’t put enough effort into evaluating. And I think this requires true human intervention, like evaluating and categorizing fraud into different categories and coming to good definitions. Like, this is what happened to this application or this consumer and putting them into those buckets: this was true third-party fraud; this was true first-party fraud. And being diligent about sampling enough of your consumer data is not just to trust the definitions you have in place but staying vigilant and trying to observe new types of fraud.

Understand that you need to be constantly updating and changing your strategies to have a real, solid KYC strategy, especially when you’re dealing with third-party fraud. You’re effectively fighting against an enemy with unlimited time and unlimited resources. The idea that they’re not going to change their strategies in response to your tactics is somewhat foolhardy. You need dedication to updating and changing.

I think KYB success relies very, very heavily on governance and process control to ensure compliance. Because the incentives of the business are not against the objectives of KYB, but they can be at odds with each other. People tend to want to get stuff done and get it done quickly. This type of governance to prevent fraud and make sure you don’t get juked is just an additional process that people need to follow.

Are there any behavioral characteristics that you think should be watched regarding how a fraudster would behave?

Behavioral fraud prevention is easily one of the most effective forms of fraud prevention.

I know what a good customer looks like, how they act, how much time they spend doing things, how often, and how they communicate with me. And I think one of the hardest things for fraudsters to determine is what the profile of a normal consumer looks like and to mirror it.

So, when you look at event tracking or behavioral tracking and building models around it, the behavioral characteristics are some of the most indicative data sources that exist to mitigate some of the more advanced fraud tactics.

Could you give an example of how a fraudster’s behavior would differ from an ordinary user’s?

They’re going to spend just different amounts of time doing different things on your application or doing different things on your site. They’re going to click their mouse in different ways. Typically, if they’re a large third-party fraud ring that needs to automate the flow through your application process, their ability to create normal patterns of traffic for large amounts of volume is going to be relatively challenging—or can be challenging for certain types of fraud.

So, the locations where they click on buttons or mouse movement, whether they tab through applications or prefill data, the types of devices they use, or the way they use those devices through the application processes, I consider all of those to be behavioral in a sense.

Kind of the sum of the parts is that you find clusters of users who tend to have behavior that is atypical. Those clusters of users tend to be related, and the relationship is usually fraud.

One of the cool things that I think more businesses should do is to not necessarily decline or weed out the fraud as early as possible. You identify it and just kind of let them do their thing, and then at the very last moment, you prevent it. That just allows you to acquire more behavioral information about the fraudsters themselves and use that for clustering or analytical purposes to identify future fraud with this same kind of risk profile.

What do you think is the single most important thing a company can do to identify potential bad actors?

I think the most important thing is to be aware of the types of fraud that exist and put great, great, great concerted effort into things like manually vetting loans, accounts, and customers that have been a part of your system for a long time. Manually reviewing them and putting actual thought into it. Is this person actually good? Is this person actually bad? And why? Categorizing things in a way that gives you better data for analysis.

You can represent uncertainty in that data and evaluate against uncertainty; that’s fine. But you have fraud, for example, that will open accounts and pay loans for nine straight months and then blow the account out, or open bank accounts and be a normal deposit user for a year and then wait for their moment and over-leverage the account.

And there are definite patterns in those accounts where you would look back and realize the stupidity of not noticing what they were doing previously. But I think it’s because people tend to think, “If I don’t have a problem at day zero, I’m going to be happy and not think more critically about this book of consumers that exist within my ecosystem.”

You have to be very vigilant about putting human effort into analysis and critical thought—really evaluating things.

.svg)

.svg)